Written by David Esch

As we reflect on our sixth project working for USAID (the United States Agency for International Development) together with our colleagues from DesignThinkers Group South Africa, I’ve been reflecting on the partnership we have built with the agency over the past four years. International development is enormously complex, and its goals are some of the loftiest you can imagine. Examples of projects include improving urban healthcare in Asia, helping countries build civil society through things like a free press and fair voting systems, and strengthening nascent entrepreneurship in West Africa. These are truly ‘wicked problems’ at massive scale, and yet that’s what makes international development a sector where design thinking can have a significant impact.

I came to DTG after a 30-year career with USAID and other international organizations. After tackling challenges in the traditional international development way for half a century, through an initiative of the Obama administration USAID began to look for new and better ways to tackle how development projects were defined, designed and funded. They started to examine internal elements such as financing, data use, policies and processes, and they looked to the private sector to find ways to drive innovation and improve development project outcomes.

The goal was lofty: could several organizations co-create a project that would reduce the number of children growing up outside of family care in Cambodian (think orphans, street children, child labor, etc.)?

DISRUPTING THE FLOW

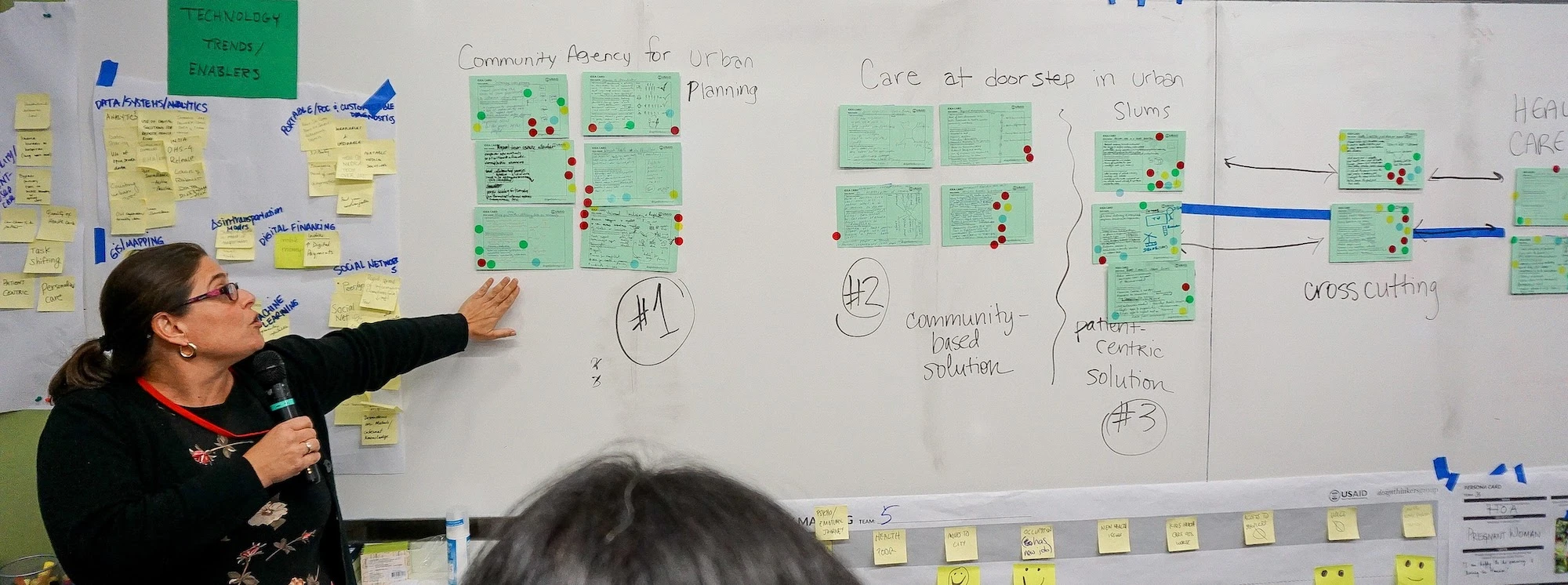

When DTG tackled its first project with USAID four years ago, the agency’s agenda included revamping the way projects were designed from the very beginning. Using a funding process that was adopted from the Department of Defense’s DARPA agency called the Broad Agency Announcement (BAA), the agency convenes experts from potential funding recipients to collaboratively define possible solutions to a complex challenge before deciding exactly who gets funded and what the outcomes or deliverables should be. The agency wanted more innovative ideas, and they wanted to explore unique partnership models – even partnerships between competing organizations – in an effort to develop and implement solutions that would have higher chances of success, and higher impact.

We assembled a team consisting of DTG staff from the U.S., the United Kingdom and the Netherlands to help prototype and test this new process by facilitating a three-day co-creation workshop with USAID in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The goal was lofty: could several organizations co-create a project that would reduce the number of children growing up outside of family care in Cambodian (think orphans, street children, child labor, etc.)?

DEVELOPING DESIGN THINKING MUSCLES

The diversity of skills and backgrounds brought together in these co-creation sessions is crucial to answering these types of questions. I recall a woman who had previously worked at Google questioning the conventional evaluation timelines. In development, three years might pass between project design, proposal and midterm or final evaluations, while at Google they might design, test, and modify a project within a matter of hours. Of course, she wasn’t implying USAID should become Google, but the difference was rather dramatic – and inspiring for the group.

Over and over again in these sessions we’ve seen professionals do in the international development world what design thinking does best: disrupt the status quo, break down the process and rebuild it based on a collaborative view and understanding of multi-stakeholder needs.

BEING HUMAN-CENTERED

Believe it or not, even with groups doing some of the most altruistic work in the world, we spend considerable time in empathy building activities during a co-creation workshop. Some participants – people who live and work on these problems day in and day out – are often, understandably, skeptical that this empathy building is a good use of time. Like many of our private sector clients, they think they know all there is to know about the people they’re trying to help.

The thing is, even compassionate development experts can get stuck in the habit of prioritizing their organizations’ goals and needs over those of those of the people they’re trying to serve. Funding, competition and everyday bureaucracy can marginalize human beings in subtle ways. Investing the time to systematically go through empathy building helps to ground co-creation participants in the key stakeholders and beneficiaries that need to be kept in focus when problem solving.

And there are added benefits to this empathy building beyond just contributing to the problem solving part of co-creation. We have seen seasoned development professionals reenergized, remembering what drew them to this kind of work in the first place. This demonstrates one of the most transformative aspects of human-centered design; it has the power to put new meaning into our work by connecting what we do to the people we are serving.

REAL PEOPLE AND TENSIONS

There’s another rather practical payoff of to keeping empathy at the center. Depending on the size of the project, USAID has brought as many as 40 or 60 people into the room. During these co-creation workshops, often lasting three long, intense days, emotions can be close to the surface.

No matter the geographic setting or the problem at hand, participants have to deal with the challenge of entering the room with preconceived ideas about what they’re going to do, then going through the social-emotional changes of collaborating to create something new and different.

DEVELOPING SOMETHING NEW

These intense, high-energy co-creation workshops that we facilitate for USAID always bring delightful surprises no matter what the specific design challenge is. Participants often surprise themselves: you should see their faces when we bring out the Legos, clay, pipe cleaners and other creative supplies and ask them to create a conceptual prototype of a policy. Despite some early skepticism, people invariably dive in and experience the magic of design prototyping, often with remarkable results.

The one thing some agencies hope to see as we document these co-creation sessions happens to be incredibly hard to capture. They want to know exactly how and when the change in perspective happens during the co-creation process. But, in reality, it is impossible to pinpoint the exact moment when a team comes up with an innovative solution. It often happens through a gradual accumulation of ideas, inputs and discussion as part of the overall human-centered design process.

There is no doubt that the trend of using co-creation in international development projects is growing and is here to stay. It leads to more innovative solutions to complex problems by tapping into the expertise of a broad range of experts. But, perhaps more importantly, if done right co-creation has a number of soft benefits like better stakeholder engagement, stronger multi-organization collaboration, and greater job satisfaction for implementers. Doing things in a new way is never easy, but using design thinking and co-creation in international development is worth the effort!